To mark International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia, Protection International (PI) interviewed two human rights defenders (HRDs) that strive to defend LGBTQIA+ rights in East Africa.

Dennis (they / them) is a lawyer who advocates for the rights of LGBTQIA+ refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya. They work closely with the transgender and gender nonconforming youth refugee community and, together with other HRDs, work to create safe houses and community-based organizations (CBOs) to protect queer refugees.

Gilbert (he / him) is an activist for LGBTQIA+ rights in Kenya. Together with his CBO Amkeni Malindi Org, he is committed to empowering the LGBTQIA+ community in his region to be comfortable with themselves and to understand the laws that exist in Kenya.

Several African countries have very poor legal protection mechanisms regarding LGBTQIA+ rights, with some of them even criminalising the LGBTQIA+ community. In particular, on 3 April 2024, Uganda’s Constitutional Court upheld the provisions of the 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act. This Act criminalises homosexuality and its recognition, promotion and financing. Organisations and individuals who promote LGBTQIA+ rights in the country can therefore be arrested and prosecuted. Dennis themselves sought asylum in Kenya some years ago after experiencing an increase in the discrimination against queer individuals in their home country of Uganda. In their opinion, “there is a big contradiction between the Anti-Homosexuality Act, the Ugandan Bill of Rights and the Ugandan Constitution. The queer population, through the Anti-Homosexuality Act, does not have access to basic services, such as legal assistance or health services, nor any kind of protection. This is why most of Uganda’s queer community has decided to leave the country“.

Such extremely restrictive legislation has an obvious impact on the environment to defend LGBTQIA+ rights, closing the space for activists to come together and carry out their activities. The situation in countries with less restrictive regulations is not always bright either. PI has conducted extensive research on the impact and coverage of HRD protection policies in DRC, for instance, and how such policies exclude some groups of defenders – including, in this case, those defending the rights of the LGBTQIA+ community. PI’s study on protection policies in the DRC found that “marginalized groups of HRDs especially face challenges in claiming protection under the protection policies in North and South Kivu. This particularly concerns environmental defenders, women HRDs (WHRDs) and HRDs working on LGBTQIA+ rights. This dual restriction on their right to defend human rights hampers their efforts“.

Kenya also criminalises homosexuality with up to 14 years of imprisonment. The country does not have any specific law to protect LGBTQIA+ individuals and Kenyan authorities have not taken a stand on LGBTQIA+ matters. According to Gilbert, non-governmental organisations and CBOs are the ones taking on the role of promoting queer (and, more broadly, human) rights in civil society. When asked to identify a particularly vulnerable community within the queer community, both HRDs agree that the transgender community is slightly more targeted by threats such as assault, death threats and evictions.

HRDs who advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights in Kenya and Uganda have challenging missions. In Kenya, HRDs are free to carry out their activism. However, according to Gilbert, “the situation of HRDs that defend queer rights in Kenya depends on which region they work in. HRDs based in cities usually work in safer environments. On the other hand, HRDs based in rural areas, where LGBTQIA+ individuals are usually seen as “outcasts” and “defenders of immorality”, often experience discrimination, self-stigma and more difficulty in accessing support networks. Overall, the situation of HRDs defending LGBTQIA+ rights is not very easy in Kenya. That is why it is so important to create platforms where HRDs build networks of support“. Gilbert highlights that the main challenges to his work as an HRD are the lack of resources, security and safety issues, being able to manage the expectations of people that you support, and engaging with supportive stakeholders.

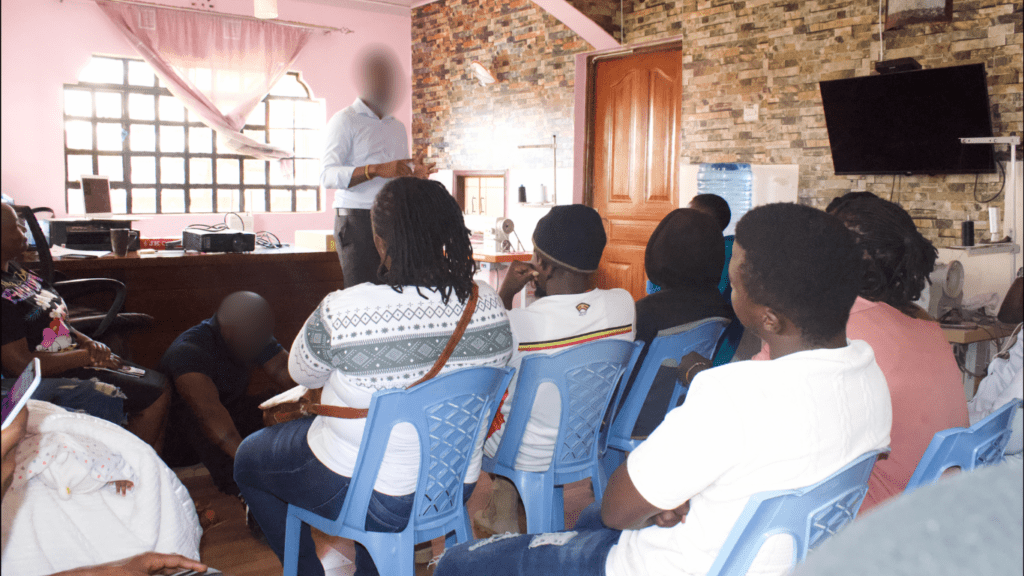

Regarding the situation of HRDs in Uganda, Dennis says that the recently passed Anti-Homosexuality Act “has enhanced the possibilities of prosecution of LGBTQIA+ persons, which has a big impact on suppressing many people’s gender identities and their sexuality. When it comes to the work of HRDs, there has been a crackdown on organisations defending LGBTQIA+ rights in Uganda. For example, some organisations have had their offices raided, their bank accounts have been blocked so that they cannot receive funding, and the funding is investigated by different departments of the police. HRDs in Uganda are working under threat and they cannot carry out public activities. For instance, events are organised in private locations, and after workshops or events, photos will be released only after a few weeks with blurred faces. Events like the Pride Parade are not allowed. You cannot hold any type of activity to celebrate people’s identity or sexuality“.

Gilbert and Dennis shared their personal experiences as HRDs who defend LGBTQIA+ rights with PI. Both reported that it is common to be the targets of verbal attacks. Still, Dennis has experienced more serious attacks. One of these occurred during an awareness-raising workshop for LGBTQIA+ refugees and asylum seekers in a shelter in Kenya. The police raided the shelter, made everyone lie down and conducted body-searches. When Dennis tried to explain the activity to the police officers, they were threatened with legal proceedings and intimidated. All the participants were taken to the police station and detained for 48 hours, which is 24 hours beyond the allowed detention time in Kenya. They were later released without any charges. Dennis reported this incident to the relevant local authorities and to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, but there was never any follow-up. In Uganda, reporting attacks against HRDs who defend LGBTQIA+ rights is not possible. According to the Anti-Homosexuality Act, anyone who relates or provides assistance to queer persons should be arrested and prosecuted. In Kenya, the reporting process is challenged by the slow response of the judicial system.

Given these challenges, Gilbert and Dennis take concrete steps to mitigate the risks that they face due to their work as HRDs. They have both taken part in protection workshops organised by PI. In Gilbert’s words, “PI has been very helpful in terms of capacity building on different topics, for instance on how best to analyze a situation as an HRD individual, digital security, resource mobilization, and finding safe spaces”. In order to mitigate the risks they face, Dennis shares that they try to be as discrete as possible in the work that they do. For example, they have reduced their activism on social media. They also relocate every few months to a new address, change their routine often, have two mobile phones and tell people whom they trust where they are going to be for safety reasons. Another measure taken by the HRD is to engage with the local police in the area where they work. “In a refugee camp, I have engaged with the authorities in order to create a positive relationship with them and raise awareness for the queer refugee community. Of course, this is a slow process, but it may reduce the level of prosecution and violence towards the refugee queer community,” says Dennis.

As for Gilbert, he has a clear list of precautionary measures, which include:

- Mapping out safe areas;

- Mapping out supportive partners and allies;

- Understanding and evaluating risks;

- Informing trusted people about what you are doing and where you are going;

- Sharing information with other allies through social media platforms;

- Cross learning;

- Ensuring that you have allies to allow continuous advocacy.

Overall, much more needs to be done to ensure the protection of HRDs who work for the defence of the rights of LGBTQIA+ individuals in Kenya and Uganda. Both Gilbert and Dennis agree that one key step would be to foster dialogue between the authorities and the queer community. There is a need for capacity building both at the central and local government level on who the LGBTQIA+ community is and who the sexual minority groups in the country are. “Without this understanding and open conversations, it will always be difficult to guarantee equal access to justice and the end of impunity for violations of human rights,” alerts Gilbert. Dennis recommends that national authorities implement an inclusive health system approach, where reproductive health is prioritised. Finally, the Ugandan HRD calls for the repeal of the Anti-Homosexuality Act and the amendment of the laws in Uganda.

Despite the challenges they face, Dennis and Gilbert are passionate about their work. The hope for a just and equal world for all is the main motivation of these HRDs, whose work for queer communities contributes to working towards a world free from homophobia, transphobia and biphobia.

PI accompanies individual and collective HRDs from the LGBTQIA+ community in different locations in East Africa, Mesoamerica and South East Asia. Back in 2010, PI published what remains the only specific protection manual for HRDs defending the rights of LGBTQIA+ people. PI remains committed to keeping its tools and resources up to date and relevant. With a forthcoming edition of its Protection Manual focusing on the safe defence of human rights, PI is also looking to update its approaches to the safe defence of rights pertaining to sexual orientation and gender identity.

*Dennis is a fictitious name in order to protect the privacy of the interviewee.